"Nothing good can come from losing our faith.

We must not fall for illusions, but keep our feet on this soil, with its mud, holes and stones.

If we want a tiny flower to grow among this desolation, we have to plant it with our hands and tend it with our love."

Lieut. Col. Pietro Testa

le

Historical background

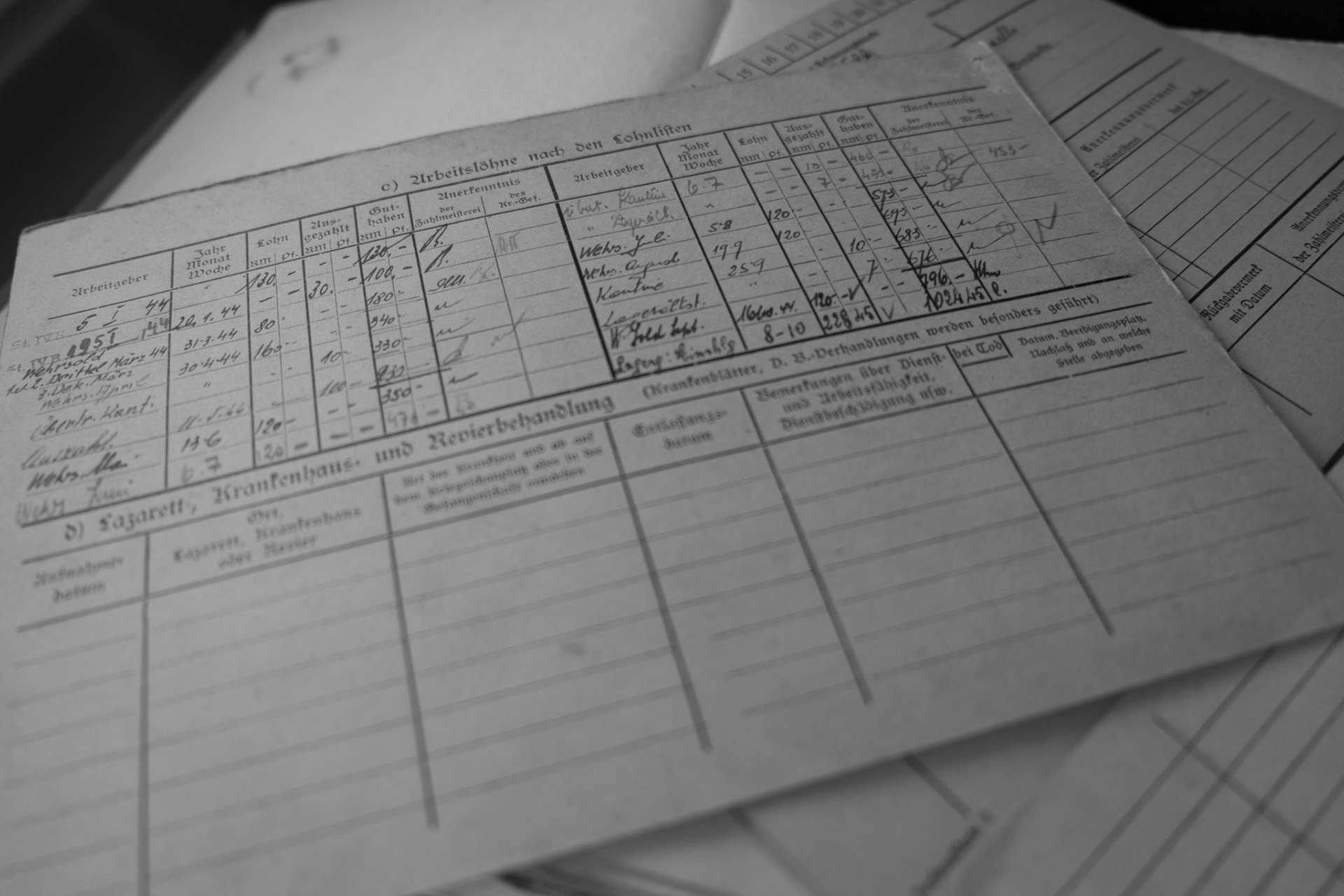

In the dark and uncertain days that followed the Cassibile armistice of September 1943 by which the Kingdom of Italy surrendered to the Allies, Italian troops were taken by surprise by Nazi Germany’s immediate and carefully-planned retaliation. Disbanded and unorganized as their king and government fled South, Italians offered little resistance to Nazi troops, who soon took control over the whole peninsula. About one million soldiers and officials were captured throughout Italy, the South of France and the Balkans. If they refused to fight on Hitler’s side, they were deported as traitors and subjected to forced labour, with no protection from the Red Cross.

My grandfather, Pietro Testa, was captured not far from his hometown: Zadar, a dazzling ancient Roman settlement on the Dalmatian coast which would be handed over to Croatia after the war, forcing thousands of Italians (including my family) to flee abroad in order to escape persecution by ferocious Ustasha. On February 9, 1944, while Zadar was being raided by yet another British bombing, he arrived in the tiny German village of Wietzendorf after a 4-month captivity in Poland which he would soon come to regret. His destination, Oflag 83, was appalling even for a trained soldier: a cluster of narrow, dark, overcrowded and unheated barracks, floating over the cold and humid moors of Lower Saxony. While digging sewage drains in an effort to sanitize the camp, Italian officials came across the remains of their predecessors: 16,000 Russian prisoners who had lost their lives there in the cold winter of 1941-1942 due to the lack of basic necessities and had been hastily buried on site before mass graves were dug a few hundred meters away.

Being the highest-ranking official on site, Lieut. Col. Testa, then aged 38, was charged with commanding his fellow Italian internees. From day one, he saw right through their inhuman treatment and daily humiliations as part of the Nazis' plan to break them into vowing allegiance to Hitler. He would have rather died than let that happen and saw to it with the highest sense of duty - through daily battles for better living conditions and against abusive punishments, but most importantly, by promoting activities that would nurture their spirits and keep them strong until Liberation day, despite the cold, the hunger and their uncertain future. The more the Nazis tried to dehumanize and push them over the edge, the stronger the Italian internees' non-violent yet unflinching resistance grew, by means of poetry and painting competitions, weekly drama representations, conferences and book exchanges. Everyone contributed with his meagre belongings and to the extent of his competences and skills, whether by teaching or crafting props with old kitchen sacks, all proud to be part of the collective effort. Thanks to Liut. Colonel Testa's relentless dedication and to the exceptional men he shared the burden with, a surprisingly high number of internees survived those 18 months of gruesome captivity and were able to witness the Italian flag being raised on camp through misty eyes, before starting the long journey back home.

A personal journey

Pietro Testa was my grandfather, but he passed away long before I was born. He was my grandmother’s hero and no day went by without her recalling his unique bravery and righteousness, her eyes lit with love and pride. He was the General in full attire staring at us from a large silver frame we all felt intimidated by. He was the beloved commander to whose widow his former comrades would come and pay their respects, softly reminiscing over a world long gone. He was my mother’s father, a heavy memory she disliked evoking and a no-speak rule we quickly learned to abide by. Who he was to me, I never allowed myself to wonder. Until one of my mother’s brothers handed me one of the few remaining copies of his war memoirs, asking me to tell this unique yet universal story so that it would not be forgotten. I flew back to Paris with the book in my purse, heavy as a stone. For months on end, I would read a couple of pages and put it back on my night table, overwhelmed by a task which seemed far out of my reach. Then my mother’s illness started to accelerate and in the void left by her passing, I felt my grandfather’s voice calling out to me, making me wonder if I had it in my guts to rise to the challenge, like he had done in much more serious circumstances.

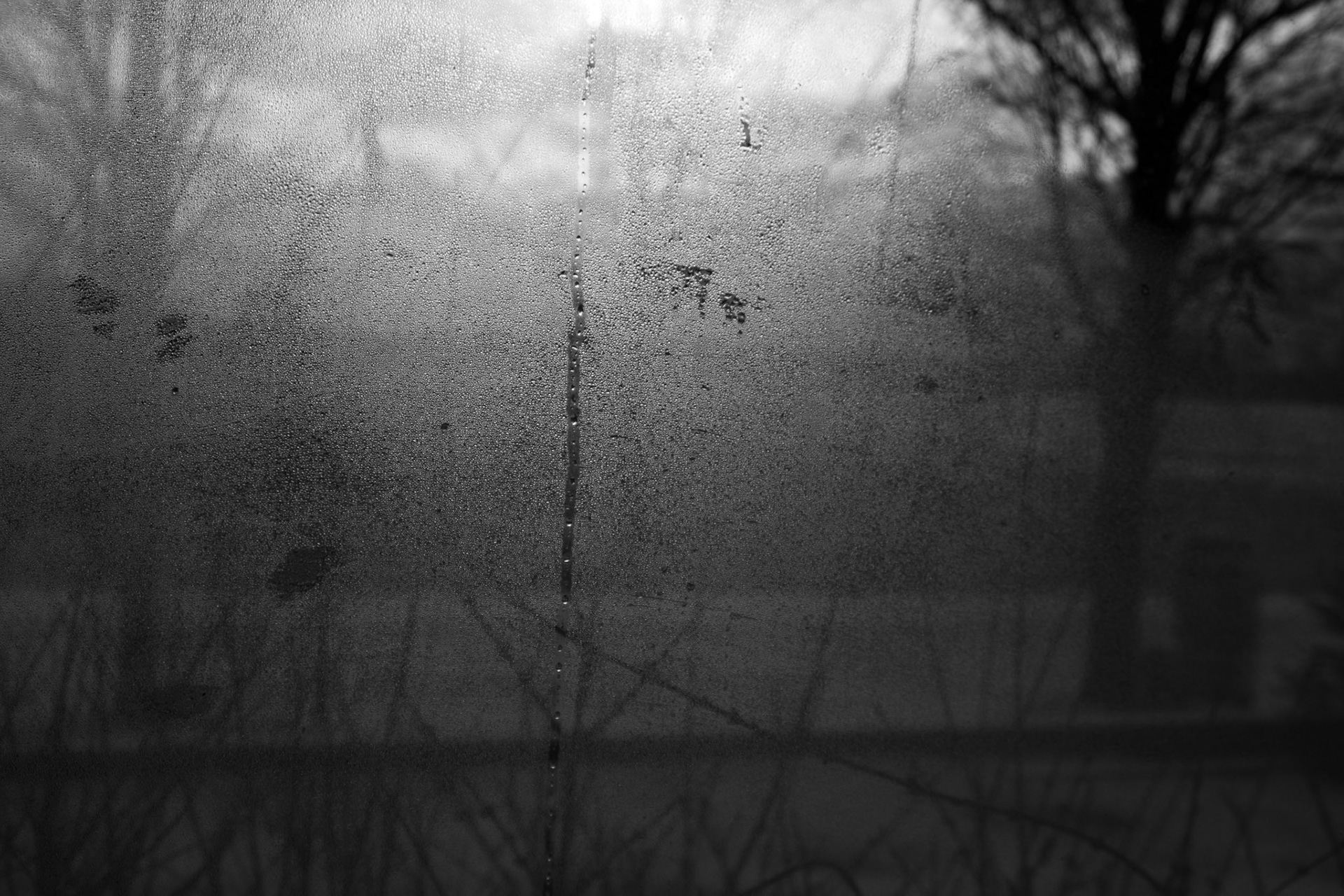

And so it happened that on a chilly February morning, I set out alone, before the light of dawn, to find the remains of Oflag 83. I knew the barracks would no longer be there, but in order to dare try and tell the story of these men’s courage, I had to leave everything behind and strive to piece together cues in a foreign language like they had had to in order to survive. Only then could I aspire to honour their memory. Little did I know how destiny would test my resolution.

After a 7-hour journey, Wietzendorf greeted me as a lovely tiny village with clean lace curtains and tended flowerbeds, as if nothing had ever happened. No signs of Oflag 83 anywhere. I was taken aback but not ready to give up and spent the day exploring the chilly countryside. As dusk set in, my bones were shaking from the cold yet I hadn't been able to locate the exact perimeter of the camp, so I locked myself up in the only open café and started searching the internet for cues. The only results led me to German material, which I was luckily able to decipher having studied Goethe's language in my youth upon my mother's strong insistence. After all those years, her prophetic insistence finally made sense by allowing me to complete the mission my family had bestowed upon me. The following day I resumed my search with new plans and a confident heart despite the short time left before my return flight. I was indeed rewarded with the much sought-after memorial stone marking the camp's entrance appearing as if by enchantment while I was driving through a parcel I had searched upon my very arrival. Given the circumstances, it made perfect sense that I would have had to strive for it.

As I finally stood on the very same ground my grandfather had marched upon on his first and last days in Wietzendorf, I knew I had come full circle. By setting out on this journey alone, as he had done, and rejoining him on that crucial spot where he had suffered for so long, aching for his beloved wife and daughter while choosing to stay loyal to his Homeland, for the first time I felt deeply connected to the man, father and grandfather I had never met.

There, as I sat in silence lighting the candles I had brought with me, these men's suffering and amazing resilience became tangible for me.

I hope this personal yet universal story moves you and inspires you to cherish even more the Light and Joy in your own life,

knowing they are fleeting and precious gifts.

Wietzendorf-Paris, February 2018

PS

Ever since I have shared this project, by the power of the internet many people have reached out to me and just like tiny flowers blossoming from that gloomy past,

enriching exchanges were born between strangers. Most preciously, with a young German scholar, Martina Wagemann, collaborating with the tourist information in Wietzendorf -

an enduring long-distance friendship I am sure my grandfather would have rejoiced in.

If you wish to visit Wietzendorf, you can reach out to:

Wietzendorf Touristik

Kampstr. 4

D-29649 Wietzendorf

Tel. 0049-5196-2190